Hydration and Training – Keys to Better Performance

February 7, 2012

By Coach Kaehler

Are you properly hydrated before, during, and after your training sessions? Do you have a hard time drinking enough plain water on a daily basis? Athletes must be diligent about hydration because they lose fluids through respiration, sweating, and excretion. Even mild dehydration can adversely affect performance. These basic guidelines will help you effectively monitor your hydration, and maximize your training and athletic performance.

For athletes, maintaining proper hydration is critical. Ideal hydration levels optimize heat dissipation, and help maintain blood plasma volume and cardiac output. By doing so, hydration reduces cardiovascular strain, and helps athletes maintain their training intensity for longer periods. Generally, you don’t feel ‘thirsty’ until your water loss reaches 1-2% of body mass. However, by this time, you’re already in an unrecognized state of dehydration or ‘hypodration,’ which can reduce training and competitive performance. Your heart rate and core body temperature becomes elevated, and you experience increased physiological strain. Althletes who train with heart rates will be able to observe this effect more clearly — their base heart rates will be higher and consequently, their workloads will be reduced due to their hypodration. As you plan your hydration routine, also consider your environmental factors. During the cold winter months, relative humidity can be significantly lower than during other times of the year. In these circumstances, you may need to increase your fluid intake.

Proper pre-exercise hydration is essential for safe and effective training and competition. A few simple signs and strategies will keep you on track for your individual hydration needs. Ensure you’re voiding every 90 to 120 minutes, and that your urine’s no darker than the color of straw. If you’re supplementing with B vitamins, you may notice a bright yellow color to your urine immediately after ingesting your vitamins. This is the only time that darker colored urine may not indicate hypohydration.

Consistently tracking your pre-training body weight is another effective way to monitor your hydration status, assuming you’re at an ideal state. Drinking 500 -600ml (17 to 20 oz) of fluids 2-3 hours before training, provides enough time to void before a training session. Then, ensure you consume another 200-300ml (6 to 8 oz) of fluids before you begin your workout. Sufficient electrolyte intake will also help you retain and regain fluid-electrolyte balance after exercise-induced dehydration, which results from excessive sweating during your training. In addition, eat regular meals 24 hours before training or competition, as a large portion of water comes directly from your food — especially from fruits and vegetables.

During training and competition, proper fluid consumption is critical for optimal athletic performance. Always ensure you have a sufficient supply of fluids available — you’ll drink more and decrease the chance of becoming dehydrated, especially in workouts lasting 30 minutes or longer. To optimize gastric emptying, consuming 12 to 16 ounces at one time is ideal. However, for some sports, such as running, too much stomach fluid can be uncomfortable. Learn and monitor your individual sweating rates during training. Although it will take time and practice, it will help you hydrate at the correct rate, and prevent serious health problems related to both under and over-hydrating.

Post-training rehydration is also essential for proper recovery, especially for longer training sessions typical of rowing. For optimal rehydration, water alone may not be the ideal beverage as it can reduce osmolality (dilutes salt concentration in blood), while decreasing the drive to drink, and increasing urine output. Also, bear in mind that absorption rates are about the same for water and fluids with a 4-8% carbohydrate concentration — making those drinks effective alternatives for rehydration. Fluids with electrolytes will also help your body retain fluids post-training. Consumption (or fluid intake) during a training session should exceed the amount of fluid lost by 1.5 times. Again, tracking your body weight just prior to and after training sessions will help you determine how much fluid to consume after your workout.

Each athlete has individual hydration needs for effective performance. Understanding and monitoring your personal hydration levels is an essential component of athletic training. Hydration is also a dynamic and on-going process. For optimal health and athletic performance, you need to plan and monitor your hydration levels not only immediately before, during and after your training, but also during the rest of your day — including your meals. Following these basic but proven-effective hydration guidelines will help you train and recover properly, and meet your athletic goals.

Are you training on an empty stomach?

October 20, 2011

By Coach Kaehler

Athletes constantly ask me whether they should eat before training, or go out on an empty stomach. Even with the extensive amount of research available today, this and many other diet and exercise-related questions remain controversial. Each individual is different. Personal differences in metabolism can skew how each of us respond to not only the food we eat, but also the timing of its consumption and how much of it we can consume.

Most of us have busy schedules. Pressed for time, many of us will either train early in the morning, or squeeze in a session during lunch. Eating around a tight schedule takes some careful planning to ensure you’re getting a quality meal in before you hit the road. If you’re an early morning riser and you don’t eat before training, you’ve most likely fasted without food for six to ten hours. If your training session is less than 90 minutes, and you’ve fueled-up your muscles and hydrated properly, chances are you won’t have a problem. If however, you’re going longer than 90 minutes, topping-off your tank 30-60 minutes before heading out is probably a good idea. If you’re preparing to do your long session in the late afternoon and your lunch time is more than four hours away from training, a snack would also make sense.

Whether you’re training in the early morning or the late afternoon, extensive research favors easy-to-digest carbohydrates that also include a small amount of protein and fat. Examples include carbohydrate gels, energy bars and sport drinks. The small amount of protein and fat in these supplements help blunt the glycemic effect (the rate at which glucose enters the blood stream) and helps maintain a steady blood glucose level. A word of caution: some recent studies have shown that ingesting high-glycemic foods 30-60 minutes before training or racing can cause a hypoglycemic effect in the blood stream. Though this low blood sugar condition does correct itself quickly, it may not be ideal before a race. On the other hand, ingesting low-glycemic foods (whole grain) just before training or racing may cause too much strain on the digestive system. Bottom-line: experiment a little. Find what works for you in terms of what food you eat, how much you eat, and when you eat it relative to your practice sessions. Experimenting and observing how your eating habits effect your performance during your practices will help you better prepare for race time.

Eating further out from training sessions alters your food options. When eating two hours before a training session, it’s still a good idea to keep your meals small and easily digestible (surf and turf may be a little too much). I would recommend liquid carbs, breakfast or training shakes with a little protein and some fat, or lighter fruits like bananas and melons. Keeping your carbohydrate intake to about 1 gram per pound of body weight is a good guideline when you’re two hours from a training session.

When you’re eating three to four hours before a training session, you can eat a full meal that includes meat. The advantages of eating three to four hours before training is that it allows your body to restore your liver glycogen to normal levels. Also, assuming you’ve consumed enough carbohydrates with your meal, this timing also allows your body to store carbohydrates into your muscles as glycogen, and minimizes the feeling of hunger during training.

Consuming the correct amount of food depends on how hard and long your training session will be, as well as the temperature of your body and its rate of heat dissipation during your session. During hard training weeks, it’s vital that you stay on top of your caloric intake as proper fueling helps your body run at maximum efficiency. Cutting calories below usage levels can alter performance and recovery during a training cycle. So if weight loss is a goal, you may observe a decrease in performance until your weight stabilizes and you get your caloric intake back to an appropriate level.

Timing your food delivery takes careful planning and preparation, but is a fundamental component of training. Building it into your daily routine will help you get optimal results from your body, and set you up for better performance on race day.

Drink Up!

April 5, 2011

Hydration and Training

By Bob Kaehler MSPT, CSCS

How closely do you follow your daily hydration intake?

The body is composed of 50-70% water (norm = 60%), and maintaining this balance is critical in regulating body temperature and cellular stasis. For endurance sports athletes, proper hydration is a key factor in effective training and race performance. A common problem with endurance athletes is hypo- or dehydration, which occurs when fluid loss is greater than intake before, during, or after bouts of exercise. When, how much, and what you combine with your water, can have a big impact on your training and race results, as well as recovery.

Whether you’re training or racing, maintaining proper hydration balance before, during, and after exercise will ensure you’re giving your body an ideal platform to work from. A reduction of total body water as small as 2% can significantly hinder your aerobic performance. One important role water plays during exercise is regulating body temperature. When a state of hypo-hydration exists, your body’s cooling efficiency is compromised. And this ‘over-heating’ leads to a reduction in your athletic performance. The Institute of Medicine recommends the following guidelines for sedentary people: men aged 19-70 y/o require 3.7L/day, while women 19-70 y/o is 2.7L/day. Hydration sources include water, other liquids, and foods. Endurance athletes however, require much greater amounts of fluids to keep their bodies properly hydrated, and must add to the above values.

To effectively plan hydration needs, athletes must also consider how long they train each day, as well as the type of climate they train in. As a general rule, for every pound of body weight lost between the start and finish of an exercise session, replace your water loss by consuming 20 ounces of fluid, or 600ml of fluid/per 0.5kg of lost body weight . One way to monitor your fluid needs would be to take your weight immediately before and after your exercise bouts, and measure the change in body mass from water loss (sweating). For those without access to lab tests, body mass change is the most effective way to self-monitor your hydration needs.

Other self assessment methods include urine color and rating of thirst. Urine color should be no darker than the color of straw, while thirst rating can be more subjective. As a general rule, keep your fluid intake consistent enough that you never feel thirsty. Taking your wake-up weight can also help you keep track of your hydration balance on a 24 hour basis by making sure your daily weight does not fluctuate. Combining wake-up weigh-ins with a body mass check right before and after training will help you accurately monitor and maintain a state of water equilibrium.

How long do you train? The length of your sessions also impacts what you should drink before, during, and after training. Training sessions lasting longer than 30-40 minutes require an intake of about four-to-six ounces of fluid every 15-20 minutes. For training sessions that exceed 60-75 minutes, sports drinks, with both carbohydrates (5-8%) and sodium, are recommended. Sweating rates for endurance athletes range from 1.2 to 1.7 liters per hour, but can be as high as 4.0 liters per hour.

For those who participate in prolonged periods of exercise (prolonged rows, marathons, or Ironman/cycling events) including electrolytes in water is critical to avoiding hyponatremia (low blood sodium levels). The typical sodium to potassium loss during exercise is 7 to 1, respectively. An athlete who loses 5L of fluid with daily training will need to replace 4,600 – 5,750mg of sodium, in addition to a seventh that amount of potassium. Fluid replacement after training must focus on restoring the weight lost from dehydration (cooling), and intake should be approximately 150% of the weight lost, or 600ml of fluid per 0.5kg of lost body weight. Post-exercise meals should also contain sodium either in food or beverages, because diuresis (fluid loss) occurs when only plain water is ingested. Most commercial carbohydrate-sodium drinks contain anywhere from 50-110mg of sodium per eight fluid ounces. Sodium assists with the rehydration process by maintaining plasma osmolality (balance) and the urge to drink.

If water becomes a boring option, try eating water-loaded foods such as water melon, cantaloupe, apples, oranges and other fruits, as well as most green vegetables. Besides keeping you hydrated, these fruits and vegetables are loaded with essential nutrients. Herbal teas and even sports drinks are another way to keep your hydration and electrolyte intake in balance. Also, remember that hydration is a 24-hour process. So spread out your fluid consumption throughout the day for better absorption into cellular tissue. The body can only process so much fluid at once, so excess will be quickly voided out of the body as urine, and will not be available for the body to use.

General hydration guidelines are as follows: 16-20 ounces of water 1-2 hours before exercise, 10 to 16 ounces 15 minutes before exercise, and about 4-6 ounces of fluid every 10-15 minutes during exercise. Fluid intake should be regulated 24 hours prior to training, so if you train daily you’re on the clock all the time. Hydration losses greater than two percent of your body weight could take up to 24 hours to restore. Research also shows that the volume of fluid intake generally increases when the water or fluid is flavored.

Bottom-line, train hard, drink-up and keep your cooling system in balance.

References:

1. Kalman DS, Lepeley A, A Review of Hydration. Strength Cond J 32:2 56-63, 2010.

2. Steve Born Hammer Nutrition, The Endurance Athlete’s Guide to Success, 2005

3. Kerksick C, Roberts M, Supplements for Endurance Athletes. Strength Cond J 32:1 55-63, 2010.

4. Maughan RJ, Leipper JB, and Sherriffs SM. Restoration of fluid balance after exercise induced dehydration: Effect of food and fluid intake. Int. J Appl Physiol 73:317, 1996

5. Monique, Ryan, 2007. Sports Nutrition for Endurance Athletes. Boulder, CO: VeloPress

Protein Supplements and Post Training Recovery

February 16, 2011

By Bob Kaehler, MSPT, CSCS

Do you take dietary protein supplements to enhance your training recovery? While much research has been done to examine how different whole food supplements affect muscle protein balance — muscle protein synthesis (MPS) vs. muscle protein breakdown (MPB) — after sessions of resistance training, one conclusion is clear. The overall success of any resistance training program is impacted by not only what you eat, but when you eat it. Muscle building and the loss of fat occur after your training is done, and by applying proper, well-informed nutritional choices, you can maximize your training efforts.

Choosing the best post- training protein supplement can be confusing. Current research shows that whey protein is superior to other whole proteins for post-workout recovery (MPS vs. MBS). Whey is a by-product of the cheese making process. If you have allergies to dairy protein, consult your physician before using it. Whey protein comes in two forms: whey isolate and whey concentrate. Whey isolate is the purest form and contains 90% or more of protein and very little (if any) fat and lactose. Whey concentrate, on the other hand, has anywhere from 29% to 89% protein depending upon the product. As the protein level in a whey product decreases, the amount of lactose and/or fat usually increases. If you purchase whey concentrate, look for at least a 70% protein level.

Researchers have also examined other common food proteins that are used for post-training recovery including egg, soy, and skim and whole milk. Egg and soy proteins also help increase muscle protein balance, though they do not achieve the same MPS levels as whey when used in post-training recovery.

If whey protein’s not for you, consider milk or soy straight out of the carton as a convenient and effective post-recovery drink. Research shows, however, that each option affects the body’s post-training recovery a little differently. Scientists examined the three beverages — skim (fat-free) milk, fat-free soy milk and a carbohydrate control beverage – to determine how each affected maximum strength, muscle fiber size (type I & II), and body composition following resistance training. Participants in the study consumed their beverages immediately after exercise, and again one hour later. While the results showed no differences in maximum strength between the groups, researchers did observe that the milk group had significantly greater increases in type II muscle fiber area and lean body mass, over the soy and control groups. Results also indicated a significantly greater decrease in the fat mass of the milk group when compared to the soy and control groups. While all the above proteins increase muscle protein balance (MPS vs MBS), whey protein, and specifically whey isolate protein, emerges as the superstar of the group as it achieves the highest levels of MPS.

Other key factors in the overall success of your training program include the timing of your recovery drink and what you combine with it. Recent studies indicate that both pre and post-training whole protein supplements produce the best muscle protein balance (MPS vs. MBS) when combined with carbohydrates. Interestingly, muscle protein balance was not affected when whey protein was taken either one-hour before or one-hour after training. The same results were not observed however with the other proteins. Specifically, amino acids (broken down whole proteins) must be taken before (60 minutes or less) training for best results.

Carbohydrate drinks are another popular post-training supplement. Again, the same rule applies here regarding the combination of protein and carbohydrates in recovery drinks. Studies once again show that protein-carbo based beverages produce significantly greater increases in total boy mass, fat-free mass and muscle strength, than drinks based only on carbohydrates.

To maximize your training recovery, the guidelines for recovery drinks are simple. Combine whole protein supplements with a carbohydrate for best results. Alternatively, if you decide to use amino acids instead of whole proteins (whey, egg, soy, or milk), take them 60 minutes before you train. If you use whey protein, you can ingest it 60 minutes before or after training with no effect on your muscle protein balance. Of all the sources of whole food protein, whey isolate is the purest and most effective in producing the best muscle protein balance. While optimal amounts of whole food and whey protein levels have yet to be clearly identified by research, some general recommendations have been proposed. For strength and power athletes consume 2 parts carbohydrates to 1 part protein, where protein intake constitutes 0.25-0.50 grams/per kg body weight. For endurance athletes, a 4:1 ratio is suggested. For those who include strength training in their training program, use a 2:1 ratio on your resistance training days, and a 4:1 ratio on your endurance/rowing training days. You can repeat this beverage intake for up to six hours after training to enhance your recovery.

Organic Recommendations

When selecting whey products, consider whey protein from grass-fed cattle. Nearly all whey protein products are a processed, isolated or a concentrated by-product of grain and soy-fed cows pumped full of hormones and antibiotics. Whey that is made from grass-fed, organic-raised cattle is exceptional for repairing tissue, building muscle, and supporting your immune system. Grass-fed cattle also produce whey that is glutamine-rich and high in Branch Chain Amino Acids and fat burning CLA.

References:

1. Tim N. Ziegenfuss, PhD, Jamie A. Landis,MD,PhD,CISSN and Robert A. Lemieux.

Protein for Sports-New Data and New Recommendations. Strength and Conditioning Journal 32 65-70, 2011

2. Hartman JW, Tang JE, Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, Lawrence RL, Fullerton AV, and Phillips SM. Consumption of fat-free milk after resistance exercise promotes greater lean mass accretion than does consumption of soy or carbohydrate in young, novice, male weightlifters. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 373-381,2007.

3. Jay R. Hoffman, PhD,FACSM,FNSCA. Protein Intake: Effect of Timing. Strength and Conditioning Journal 29:6 26-34, 2007

4. Kyle Brown, CSCS – Post Workout Recovery Nutrition: It’s Not What You Digest But What You Absorb That Counts. NSCA’s Performance Training Journal. 8:6 6-7, 2009

Grass-Fed Beef

January 21, 2011

A study done in Australia in 2006 tested different cuts of beef from both grass-fed and grain-fed cattle. Researchers concluded that the grass-fed beef had higher levels of two types of healthy fat — omega-3’s( which reduce inflammation in the body) and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Grass-fed beef was also found to have lower amounts of saturated fats (bad oils) when compared to grain-fed cattle. Grass-fed beef tends to be tougher than grain-fed cuts(marbleized beef), however it can be much more flavorful. Look for an upcoming piece which will include recipe and cooking instructions on how to prepare grass-fed beef.

** STUDY Effect of feeding systems on omega-3 fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid and trans fatty acids in Australian beef cuts:potential impact on human health

ERIC N PONNAMPALAM, NEIL J MANN AND ANDREW J SINCLAIR

Water Guidelines for Training Recovery

February 5, 2010

Water Guidelines

Fluid replacement in and around meals:

Proper hydration is an important element of recovery from training. Male endurance athletes can lose up to 10 liters of fluid per day, while women lose slightly less. Daily individual losses vary depending on the training climate, as well as the length and intensity of training. Water levels can be balanced through the water you drink, as well as the food you eat. To optimize your recovery, you must consider when to replace your fluids, as well as how the fluids are delivered to your digestive system. Here are some basic guidelines for fluid replacement in and around your meals.

Timing

Recovery from training is optimized when the body can devote most of its energy into rebuilding itself. Avoid drinking liquids with meals as it requires the body to secrete additional digestive enzymes which slows digestion and reduces its efficiency.

When recovering from training, avoid drinking water 30 minutes prior to eating, and for about 2 hours after a carbohydrate meal, and up to 3 hours after a heavy protein meal.

How to rehydrate

When eating protein meals, include plenty of raw vegetables (salads) as they are made mostly of water. With carbohydrate meals, include plenty of raw fruit as they too are mainly made of water. The water in fruit and vegetables does not dilute digestive enzymes, so it is the most efficient delivery of water back into the body when eating.

One method of fluid replacement that I prefer is eating fresh melons as a snack in between meals. Melons digest very quickly (about 30 minutes) and they are about 90% water. The digestion of the melons slows the delivery of water into the bloodstream, which is easier on the kidneys.

Overall, ensure you drink enough water between meals, and increase your consumption of raw fruit and vegetables.

Proper and balanced hydration is a critical factor in optimizing your training and racing.

All About Energy Balance

January 21, 2010

What is energy balance?

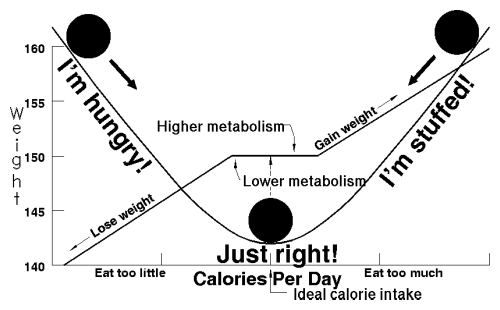

“Energy balance” is the relationship between “energy in” (food calories taken into the body through food and drink) and “energy out” (calories being used in the body for our daily energy requirements).

This relationship, which is defined by the laws of thermodynamics, dictates whether weight is lost, gained, or remains the same.

According to these laws, energy is never really created and it’s never really destroyed. Rather, energy is transferred between entities.

We convert potential energy that’s stored within our food (measured in Calories or kcals) into three major “destinations”: work, heat and storage.

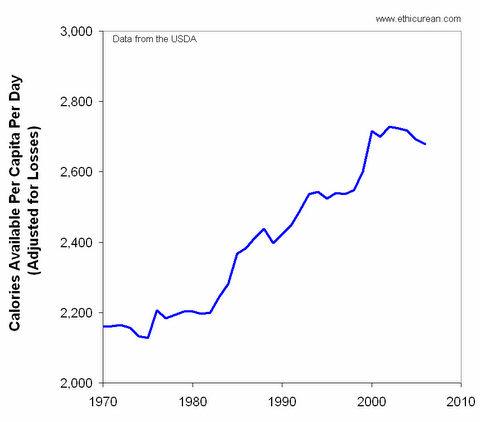

As the image below shows, the average number of available calories per person in the US is increasing. In general, there is more “energy in”.

When it comes to “energy out,” the body’s energy needs include the amount of energy required for maintenance at rest, physical activity and movement, and for food digestion, absorption, and transport.

We can estimate our energy needs by measuring the amount of oxygen we consume. We eat, we digest, we absorb, we circulate, we store, we transfer energy, we burn the energy, and then we repeat.

Why energy balance is so important

There’s a lot more to energy balance than a change in body weight.

Energy balance also has to do with what’s going on in your cells. When you’re in a positive energy balance (more in than out) and when you’re in a negative energy balance (more out than in), everything from your metabolism, to your hormonal balance, to your mood is impacted.

Negative energy balance

A severe negative energy balance can lead to a decline in metabolism, decreases in bone mass, reductions in thyroid hormones, reductions in testosterone levels, an inability to concentrate, and a reduction in physical performance.

Yet a negative energy balance does lead to weight loss. The body detects an energy “deficit” and fat reserves are called upon to make up the difference.

The body doesn’t know the difference between a strict diet monitored by a physician at a Beverly Hills spa and simply running out of food in a poor African village. The body just knows it isn’t getting enough energy, so it will begin to slow down (or shut down) all “non-survival” functions.

Ask somebody who has been fasting for two weeks if they have a high sex drive. Nope.

Positive energy balance

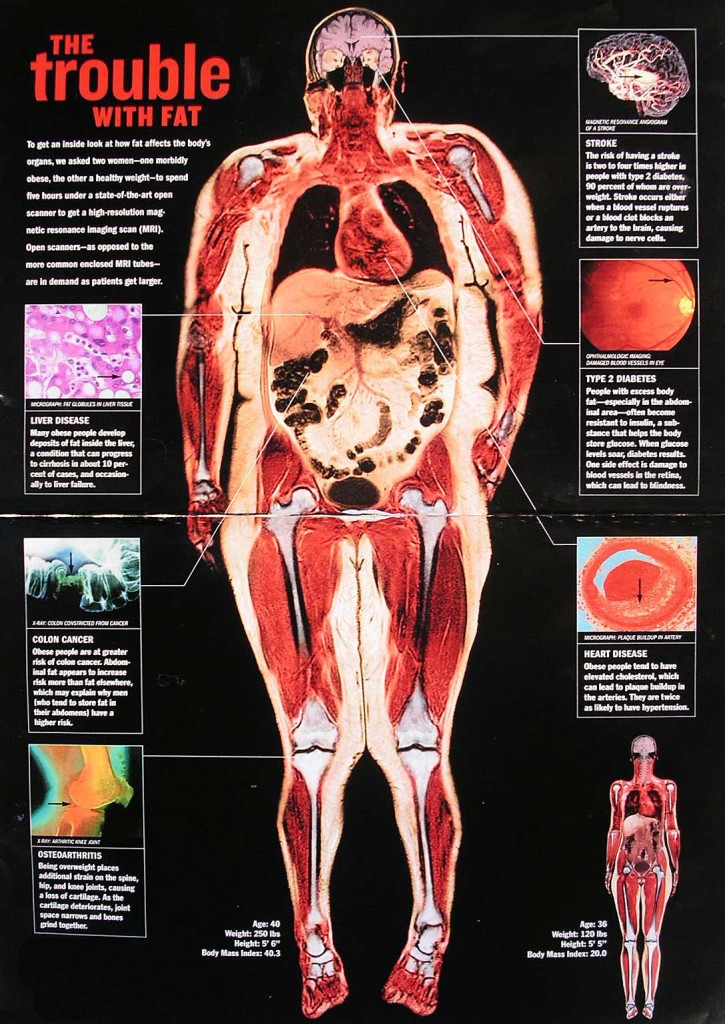

Overfeeding (and/or under exercising) has its own ramifications not only in terms of weight gain but in terms of health and cellular fitness.

With too much overfeeding, plaques can build up in arteries, the blood pressure and cholesterol in our body can increase, we can become insulin resistant and suffer from diabetes, we can increase our risk for certain cancers, and so on.

The relationship between the amount of Calories we eat in the diet and the amount of energy we use in the body determines our body weight and overall health.

The body is highly adaptable to a variety of energy intakes/outputs. It must be adaptable in order to survive. Therefore, mechanisms are in place to ensure stable energy transfer regardless of whether energy imbalances exist.

What you should know about energy balance

The standard “textbook” view of energy balance doesn’t offer consistent explanations for body composition changes.

This is because calorie restriction or overconsumption without a “metabolic intervention” (such as exercise or drugs) is likely to produce equal losses in lean mass and fat mass with restriction or equal gains in lean mass and fat mass with overfeeding.

People will likely end up as smaller or larger versions of the same shape. They’ll lose muscle along with fat.

Both sides of the energy balance equation are complex and the interrelationships determine body composition and health outcomes.

Gone are the days of eating a 1500 calorie meal from McDonald’s and then “exercising” it off. Overall lifestyle habits help to properly control energy balance, and when properly controlled, excessive swings in either direction (positive or negative) are prevented and the body can either lose fat or gain lean mass in a healthy way.

Factors that affect energy in

|

||

| Factors that affect energy out | ||

Work

|

Heat

|

Storage

|

Why do people struggle to get negative or positive?

First and foremost, it’s uncomfortable.

But furthermore, an interesting phenomenon has developed over the past 25 years.

With our focus on specific nutrients, intense dietary counseling, repeated dieting and processed food consumption, body fat levels have also increased. While nutrition and health experts simply blame weight gain on calories, that doesn’t paint the whole picture.

Blaming weight gain on calories is like blaming wars on guns. The calories from food are not the sole cause of a skewed energy balance. It’s the entire lifestyle and environment.

While this may seem illogical, it demonstrates the importance of body awareness (hunger/satiety), avoidance of processed foods, regular physical activity and the persuasion of advertising.

Is calorie counting the solution? Probably not

Many people feel that if they just can add up calorie totals for the day, their energy imbalance problems will be solved.

While it can work for some and even make others feel proud of their spreadsheet skillz, by the time we add up calories for the day and factor in visual error, variations in soil quality, variations in growing methods, changes in packaging, and assimilation by the body – do we really know how many actual calories have been consumed? I sure don’t, and I’m a dietitian.

Our energy balance is regulated and monitored by a rich network of systems.

There’s a complex interplay between the hypothalamus, neural connections in the body and hormone receptors. Information is received about energy repletion/depletion, the diurnal clock, physical activity level, reproductive cycle, developmental state, and acute and chronic stressors.

Moreover, information about the acquisition, storage, and retrieval of sensory and internal food experiences are relayed. These signals can impact energy balance. Even the best spreadsheet skills will have trouble tracking that.

As a society, the more we focus on calories and dietary restraint, the more positive our energy balance seems to get.

So, what should we focus on?

How about considering ingredients rather than nutrition facts labels?

One of the most uncool 100 calories around

The nutrition facts label is pretty worthless until we know what we’re eating. 100 calories isn’t cool when it’s Chips Ahoy. So, if monitoring is your thing, then monitor food quality more that quantity.

Straight up overeating

Don’t kid yourself: it’s still possible to overeat “quality” food. However, this overeating takes place usually when we’re “sneaking” calories in by choosing high calorie density foods.

- For example, by using 2 tbsp of olive oil to prepare our meals 3x per day, we can “sneak in” over 90g of fat and 810 calories into our diets. Olive oil is good for us. But adding 810 calories per day probably isn’t.

- Further, if we eat 4 handfuls of mixed nuts per day, which may be an extra 300-500 calories, depending on the size of your hands. Again, raw nuts are awesome for us. However, eating too many isn’t.

- If we go with 4 whole eggs for breakfast, instead of 3 egg whites and 1 whole egg, that’s an extra 18g of fat and 162 calories.

- If we choose lean protein vs. extra lean, we may add an additional few hundred calories of fat to our menu each day without even knowing it.

As you can see from the above, in most cases, we wouldn’t really be able to tell the difference between our meals with and without the olive oil, with extra lean vs. lean, and so on.

In essence, we’re sneaking the extra calories in without being any more full, and/or without changing anything else about our day. And that’s when it’s possible to over-eat on nutritious foods.

So, although we discourage counting calories, grams, etc. we do suggest watching out for calorie sneaking.

All of these plates contain 200 calories

How to be negative or positive

While necessary for fat loss, a negative energy balance can be uncomfortable. Being in a negative energy state can result in hunger, agitation, and even slight sleep problems.

On the flip side, while necessary for muscle gain, a positive energy balance can be uncomfortable as well. Both extremes cause the body to get out of, well, balance.

Accomplishing a negative energy balance can be done in different ways.

Increasing the amount of weekly physical activity you participate in is one of the best options.

How to create a negative energy balance

- Build muscle with weight training (about 5 hours of total exercise each week) and proper nutrition

- Create muscle damage with intense weight training

- Maximize post workout energy expenditure by using high intensity exercise

- Regular program change to force new stimuli and adaptations

- Boost non-exercise physical activity

- Increase thermic effect of feeding by increasing unprocessed food intake

- Eat at regular intervals throughout the day

- Eat lean protein at regular intervals throughout the day

- Eat vegetables and/or fruit at regular intervals

- Incorporate omega-3 fats

- Incorporate multiple exercise modes

- Stay involved with “life” outside of exercise and nutrition

- Sleep 7-9 hours each night

- Don’t engage in extreme diets for risk of long-term overcompensation

- Stay consistent with habits

- Ignore food advertising

How to create a positive energy balance

- Build muscle with weight training (at least 4 hours of intense exercise per week) and proper nutrition

- Create muscle damage with intense weight training

- Minimize other forms of exercise (other than high intensity and resistance training)

- Limit excessive non-exercise physical activity

- Try consuming more shakes and liquids with calories

- Build in energy dense foods that don’t cause rapid satiety (nut butters, nuts, trail mix, oils, etc.)

- Eat at regular intervals throughout the day

- Incorporate additional omega-3 fats

- Take advantage of peri-workout nutrition, with plenty of nutrients consumed before, during, and after exercise

- Sleep 7-9 hours per night

- Stay consistent with habits

Remember that a skewed energy balance is not something that needs to be achieved from now until the end of time. Once in “maintenance mode,” constant energy balance excursions are unnecessary.

Further resources

http://www.precisionnutrition.com/members/showthread.php?t=8265

Extra credit

Micronutrients act as cofactors and/or coenzymes in the liberation of energy from food. A limited intake can disturb energy balance and can lead to numerous side effects.

Some factors that have been associated with attaining a negative energy balance include:

- Regular nut consumption

- Meal replacement supplements/super shakes

- Green tea

- Low energy density foods (veggies, fruits, lean proteins, whole grains, etc.)

- Dietary protein

- Avoidance of refined carbohydrates

- Adequate hydration

- Dietary fiber

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Regular exercise

- Adequate sleep

- Positive social support

References

Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, 3rd Edition. Groff JL, Gropper SS. 1999. Delmar Publishers, Inc.

Anatomy & Physiology, 4th Edition. Thibodeau GA, Patton KT. 1999. Mosby, Inc.

Exercise Endocrinology, 2nd Edition. Borer KT. 2003. Human Kinetics.

Illustrated Principles of Exercise Physiology, 1st Edition. Axen K, Axen KV. 2001. Prentice Hall.

Food, Nutrition & Diet Therapy, 11th Edition. Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S. 2004. Saunders.

Nutrition and Diagnosis-Related Care, 5th Edition. Escott-Stump S. 2002. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

The Merck Manual, 17th Edition. Beers MH, Berkow R. 1999. Merck Research Laboratories.

Forbes GB. Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;904:359.

Prentice A, Jebb S. Energy intake/physical activity interactions in the homeostasis of body weight regulation. Nutr Rev 2004;62:S98.

Rampone AJ, Reynolds PJ. Obesity: thermodynamic principles in perspective. Life Sci 1988;43:93.

Berthoud HR. Multiple neural systems controlling food intake and body weight. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2002;26:393.

Jequier E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann NY Acad Sci 2002;967:379.

Buchholz AC, Schoeller DA. Is a calorie a calorie? Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:899S.

Nutrition and the Strength Athlete. Volek, J. 2001. Chapter 2. Edited by Catherine G. Ratzin Jackson. CRC Press.

Essen-Gustavsson B & Tesch PA. Glycogen and triglycerides utilization in relation to muscle metabolic characteristics in men performing heavy resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 1990;61:5.

MacDougall JD, Ray S, McCartney N, Sale D, Lee P, Gardner S. Substrate utilization during weightlifting. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1988;20:S66.

Tesch PA, Colliander EB, Kaiser P. Muscle Metabolism during intense, heavy resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 1986;55:362.

Cori CF. The fate of sugar in the animal body. I. The rate of absorption of hexoses and pentoses from the intestinal tract. J Biol Chem 1925;66:691.

Nutrition for Sport and Exercise, 2nd Edition. Berning J & Steen S. Chapter 2. 1998. Aspen Publication.

Pitkanen H, Nykanen T, Knuutinen J, Lahti K, Keinanen O, Alen M, Komi P, Mero A. Free Amino Acid pool and Muscle Protein Balance after Resistance Exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:784.

Ivy JL. Muscle glycogen synthesis before and after exercise. Sports Med 1977;11:6.

Chandler RM, Byrne HK, Patterson JG, Ivy JL. Dietary supplements affect the anabolic hormones after weight-training exercise. J Appl Physiol 1994;76:839.

Ganong WF (2001) Endocrine functions of the pancreas & regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. In: Review of Medical Physiology. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 322-343.

Guyton AC, Hall JE (2000) Insulin, glucagon, and diabetes mellitus. In: Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, pp. 884-898.

Jentjens R & Jeukendrup A. Determinants of Post-Exercise Glycogen Synthesis during short term recovery. Sports Med 2003;33:117.

Levenhagen DK, Gresham JD, Carlson MG, Maron DJ, Borel MJ, Flakoll PJ. Postexercise nutrient intake timing in humans is critical to recovery of leg glucose and protein homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;280:E982.

Borsheim E, Tipton KD, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR. Essential amino acids and muscle protein recovery from resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002;283:E648.

Mattes RD, et al. Impact of peanuts and tree nuts on body weight and healthy weight loss in adults. J Nutr 2008;138:1741S-1745S.

Berthoud HR. Multiple neural systems controlling food intake and body weight. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2002;26:393-428.

Stice E, et al. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: a prospective study. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2005;73:195-202.

Shunk JA & Birch LL. Girls at risk for overweight at age 5 are at risk for dietary restraint, disinhibited overeating, weight concerns, and greater weight gain from 5 to 9 years. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:1120-1126.

Tanofsky-Kraff M, et al. A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:1203-1209.

Optimum Performance and the Use of Caffeine

January 11, 2009

Do you grab a quick caffeinated beverage before racing, or chug a caffeinated sports drink during your workout? Many athletes believe consuming a shot or two of caffeine is an ideal way to get that quick boost of energy in the quest for better performance. However the effects of caffeine on your endurance training may not be giving you the results you are looking for. Of course, many people use caffeine throughout their day to help stimulate them during daily activities and energize them during their workouts. Understanding the effects that caffeine has on a body is important in deciding whether or not to use caffeine as part of your training program.

Caffeine is actually a toxic stimulant found in nature. Although it revs the body up, it provides zero in terms of energy. After ingesting caffeine, your body automatically begins the process of metabolizing (getting rid of) it. This metabolic activity actually costs you energy and takes it from your storage of nutrients. Therefore a stimulant like caffeine triggers an abnormal “speeding up” reaction to begin eliminating it. This “speeding up” is the caffeine buzz you feel, but in actuality it is depleting your body of necessary energy and nutrients.

Not only does the process of metabolizing caffeine use up energy, it has diuretic effects (fluid loss) as the body tries to clear it from your system. This creates a negative water balance in your body, leading you to urinate more. Coupled with the elevated heart rate usually caused by caffeine, the diuretic effect could lead to over-stimulation of your body, potentially leading to dehydration in people already pushed to their physical limits. During this process of elimination we can be fooled into thinking that the stimulant is an energy value, when really it is an energy cost.

A recent article published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, titled “Caffeine and Endurance Performance”, by Matthew S. Ganio, et al., is a systematic review of 21 different studies which measured performance with a time-trial test. They looked at endurance events that were at least five (5) minutes or longer, such as cycling, running, etc. The authors of this study concluded that although the performance improvements were varied among the studies researched, they found that factors including timing, ingestion mode/vehicle, and subject habituation may have influenced study results.

One significant recommendation Ganio, et al., made from this review was that endurance athletes abstain from caffeine use at least seven (7) days before competition to maximize its ergogenic (boosting) effect. Also, it was noted by Ganio, et al. that if caffeine is used for an ergogenic effect, it should be ingested within 60 minutes or less of competition or training. The amount of caffeine commonly shown to improve endurance performance is between 3 and 6 mg. per kg-1 body mass. The caffeine benefit was equally effective when consumed with a carbohydrate solution, gum, or water alone, however coffee was noted to not to be as effective a caffeine source. When caffeine is used on a regular basis, the ergogenic effect is not as great, compared to using it sporadically or not at all.

Overall, chronic use of caffeine appears to have far less effective results in time-trial testing, and appears to cost the body energy and nutrients in elimination from the body on a daily basis. However, should an athlete decide that caffeine use is beneficial, it would make sense to follow the guidelines for amounts ingested and limit use during time trials spaced seven days or more apart, prior to race day. Determining the best use of caffeine, if any, is a personal decision best made with the advice of your physician and coach.

Before grabbing that caffeinated sports drink, consider the effects of caffeine on your body. Because of the generally negative effect that metabolizing caffeine has on a body, Coach Kaehler does not advocate the use of caffeine as a regular part of a training program. Instead, he believes that a well balanced, specially designed training and nutrition program is much more effective for achieving the maximum performance results desired on race day.

Coach Kaehler has posted this for informational purposes only, and that the use of caffeine for performance enhancement is a personal preference. It should be noted, however, that he does not recommend the use of caffeine for the clients he trains.

Harmful Food Oils

January 6, 2009

Any ingredient that has the word “partially” or “partially hydrogenated” in it can basically be considered toxic for healthy bodies. Often marketed as “trans-fats”, these types of oils, including partially hydrogenated palm oil and partially hydrogenated soybean oil, are usually found in many “man-made” processed foods, such as cookies, crackers, margarine, and salad dressings. These oils are chemically altered to prevent them from going rancid, thus extending their shelf life, resulting in cheaper prices for consumers and increased profits for food manufacturers. Be aware that tropical oils such as palm oil, coconut oil, grapeseed oil, and cottonseed oil may also be hydrogenated as well, and therefore, unhealthy food choices.

According to the book, Conscious Health, by Ron Garner, the process of hydrogenation destroys the enzymes, nutrients, and vitamins present in natural oils. Hydrogenated oils have been strongly linked to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other serious health problems1 by lowering the body’s good cholesterol (HDL) and increasing its bad cholesterol (LDL).

For the conscientious athlete, it is much wiser and healthier to shop where natural, unprocessed foods are readily available, in places such as Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s, health food stores, and local farm markets. If you must shop at a conventional food store, pay close attention to the labels and look for organic or minimally processed foods without hydrogenated oils. Making healthier food choices today will benefit your healthy body tomorrow.

1 Erasmus, Udo. Choosing the Right Fats. 2001. pp.10,11. http://alive.com

Pre-race Meal

December 13, 2008

You must complete your pre-race fueling three or more hours prior to the start because the insulin-induced blood sugar level “disruption” from a pre-race meal lasts about three hours before hormonal balance is restored.

Taking in a bagel and banana while they are okay to eat three hours prior to the race are not a good idea to eat one hour prior to the race. This meal will rapidly elevate blood sugar levels, which will create an excess of insulin released into the blood stream which leads to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). This would be okay to consume right after a workout because of enzymes released from the exercise would dampen this effect, but since you are eating this meal without any pre-ceding activity this is not a good idea.

Also, this high insulin level so close to the race does inhibit lipid mobilization during aerobic exercise which will reduce fats-to fuel conversion capabilities. Since roughly 60-65% of your energy will come from fats once your 60-90 minute store of muscle glycogen is used up we need this system to be working at a maximum. The remaining 35-40% of your fuel comes from the gel packs. Another big reason to not eat so close to the race is because these high insulin levels induce a sugar influx into the muscle cells, which increases the rate of carbohydrate metabolism. What this does is deplete your muscle glycogen much quicker than if you keep your meal three hours out. It takes about three hours for your body to restore normal hormonal balance with a pre-race meal done with no exercise prior to the meal.

If you feel you absolutely must eat, consume 100 – 200 calories about five minutes before start time. By the time these calories are digested and blood sugar levels are elevated, you’ll be well into your race and glycogen depletion rates will not be negatively affected. This strategy is especially appropriate for triathletes who will hit the water first