Posture and Rowing

August 25, 2011

By Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Posture is a culmination of life’s activities and tendencies. At the same time, our posture inevitably reflects our effort and commitment to improving it, or in some cases not. While ideal posture is different for each person, there are some key body alignment areas that are certain positions. For example when your back is against a wall your ears should be directly over the shoulder joint and your head should be touching the wall with your chin parallel to the ground. Infants and toddlers start out with a clean slate, and have an ideal body alignment from the get-go. They are flexible and strong at the same time. Like a world-class Olympic lifter, they can easily get into positions that many would cringe at. Barring any genetic or birth defect, the fact is that most of us could still easily get into these ideal positions if we had perfect posture. So what happened? Life, gravity, and normal daily activities. They slowly undermine our clean-slate posture. Fortunately, one thing I have learned through my years of practice is that we are capable of restoring much of the flexibility and strength we once had through hard, consistent work and a solid well-balanced plan.

Gravity creates a constant pull on the body when we are standing, sitting, or rowing in a boat. Years of postural neglect lead to the development of poor postural habits, and the inability to maintain good posture for more than a few moments. Poor standing posture only gets worse when you get in a boat. When we stand, our hips are free to move forward and back as we do in daily activities. However, in a boat, we lose this ability and the hips shift the force to other areas of the body, namely the trunk and lower extremities. Keeping the spine in a good upright position then becomes difficult and tiring, especially when you have flexibility and strength limitations. A common rowing posture is what I call the “turtle shell”, or “rounded” position, where the spine (low and mid-back) are flexed or rounded. This spine position places increased stress on the passive tissues of the spine and ribs (discs, ligament, and bone). While the spine is amazingly resilient, prolonged periods of rowing at high intensity and volumes ultimately lead to back and rib injuries.

To improve posture, flexibility is always the priority and must be addressed first. I like to say “if you can’t get there, you can’t strengthen it”. Having excellent range of motion helps athletes get into ideal sporting positions. In rowing, two critical areas for flexibility are in the hamstrings and the latissimus muscles. Tightness in either area or both leads to the likelihood of rowing in the rounded back position. The drive of the rowing stroke is essentially a horizontal Olympic power clean. I use this movement as my model for flexibility, strength, and spine position, to help rowers develop maximum power with least chance for injury. The only difference between the rowing stroke and Olympic power clean (aside from horizontal vs. vertical) is that in rowing our hips are not free to move (seat). This fact alone (hips fixed by the seat) leads to a greater need of flexibility, and is also the reason why we can’t get the spine into a fully extended (curved or lordotic) position during a rowing stroke.

Strength is also an important consideration for maintaining better rowing posture. Without a conscious effort to maintain good posture in the boat, most rowers slump down into the rounded position. This position is easiest to maintain because it requires little to no energy to maintain it. As flexibility improves, it becomes easier to strengthen the spine into an extended position. Strengthening the spine against gravity (in standing) is an excellent way to help promote a more extended or straight position of the trunk/spine in the boat.

Making the shift to better posture requires considerable work and effort, but becomes habit over time. Sitting upright then becomes second-nature. There are two very effective exercises that can be used for both improving flexibility and strength, and target the hamstrings, lats and spine. The first is the straight leg dead lift which targets the hamstrings, glutes and back extensor muscles. This exercise can be used to stretch the hamstrings using a dowel or stick, or as an exercise to improve strength in the hamstrings, glutes and back extensor muscles by using a barbell or dumbbells. The other exercise is the overhead squat which is a great way to stretch out the lats. If weight is added (barbell), this exercise increases strength in the low back, quads, glutes, hamstrings, trunk and other muscles. Proper coaching instruction will help maximize the results from these two lifting techniques. Both exercises can be used as either a stretching or strengthening exercise to improve your posture both on land and in the boat.

Ideal posture will not only translate into more effective, efficient and powerful rowing, but will also extend into all your day-to-day activities of our lives outside the boat. So sit-up, stand-tall, and make a conscious and balanced effort to improving your posture.

Straight Leg Dead Lift - Start Position

Straight Leg Dead Lift - Finish Position

Pushing Your Comfort Zone

June 22, 2011

By Bob Kaehler

A little planning goes a long way in injury prevention

Rowing has its share of overuse injuries. Factors that increase your risk of injury include: changing training volume or intensity too quickly, and allowing too little recovery time during and between during training sessions. Other contributing factors include improper technique, poor flexibility and strength, and inadequate nutrition. Careful planning and learning to listen to your body’s signals are essential to minimizing the impact of overuse injuries.

Training outside of your comfort zone

Experiencing pain is a necessary evil of endurance training, especially when you’re training outside of your comfort zone — your usual training approach that doesn’t exceed or challenge your physiological limitations. Pushing yourself out of your comfort zone is critical for developing your physical and mental capacity, as well as improving your lactate buffering capacity or VO2 max. Often, when pain does show up, the brain goes into survival mode and tells you to keep going — that the pain will go away. While some athletes will immediately stop their activities and get themselves checked out, others will train through the initial signs of pain and enter an uncomfortable zone. However, when pain is long-lasting, we have to use it as a “coach” that is telling you something is wrong. When we ignore the initial symptoms and train into an uncomfortable zone, we place ourselves at risk of sustaining injuries of greater magnitude.

Training volume and injury risk

Numerous studies conducted on running athletes have examined the relationship between mileage and injury rate. Once running mileage exceeds about 20-25 miles per week, studies indicate that the rate of injury increases significantly. While I’m not aware of any studies focused specifically on the relationship between rowing volume and training-related injuries, I have made similar observations based on my own coaching and conditioning experience. Masters and junior-level rowers who exceed about four to five hours of rowing per week seem to sustain a noticeable jump in their rate of injuries. Collegiate and high-level club rowers seem to be able to handle about twice that amount (eight-to-10 hours per week) of training before sustaining a similar increase in training-related injuries. Large changes in training volume in short periods of time also trigger increases in injury. This often explains why coaches notice increases in injury rates when high school rowers begin their collegiate careers, or when college rowers start training with the National Team.

Training transitions: Understand expectations and be prepared

When you’re transitioning to the next level of your endurance sport, understand what will be expected of you and plan ahead. What will be your new normal weekly training volume and intensity? This information will help you determine how to increase your conditioning in a controlled and safe manner. Preparing your body to accept new training loads and training volume is a critical component to reducing your risk of training-related injuries. The general consensus for increasing exercise volume and intensity (I also use this guideline in my coaching and conditioning) is to increase training volume by no more than 10% per week. In my practice I do not increase training intensity by more than 10% per week, and often times it is less than 10%. In rowing, training volume is easy to measure, and intensity can be measured by using watts on the ergometer, or by measuring speed in the boat. The same guidelines apply to increases in rating — no more than a 10% increase per week. Similarly, for running and cycling, we can use speed as the best measurement to control intensity, and mileage for volume. For cycling, we can use wattage and speed.

Technique can also break down from fatigue when program volume and intensity change too quickly, or when deficits in strength and flexibility do not allow the athlete to get into proper sport specific positions for their sport. Both of these issues can lead to overuse training injuries. Building yourself up carefully and gradually, with consistent and small increases in training volume and intensity is the safest and most effective way to accept new loads and stresses on the body, and minimize your risk of injury.

Muscle and flexibility imbalances

Musculoskeletal pain is a common byproduct of endurance training, especially as intensity increases or if strength training is used. Flexibility and strength requirements vary amongst endurance sports and when not properly addressed, can be a recipe for disaster when training volume and intensity increase, and can lead to training-related pain. Imbalances in flexibility and strength can actually get worse as an athlete shifts from a low volume and low intensity training program (less than five hours/per week), to a higher volume and higher intensity training program. Paying attention to these imbalances is important for all levels, but is often neglected when there are no signs. When musculoskeletal training pain does arise and doesn’t go away quickly (two or three days) or gets worse, stop your program and get checked out by a sports medicine professional. This is a clear example of when not to train out of your comfort zone, as it often leads to a more significant injury with a longer recovery time.

Many endurance athletes do not realize how close they are to sustaining training-related injuries and continue to train in their comfort zone. When you have no training-related pain, it is easy to skip the detail work — proper stretching and strengthening – and just keep doing what you’re doing. Manipulating training volume and intensity must be done slowly and carefully at all levels of experience with a carefully laid-out plan. In addition, both coaches and athletes need to be aware of individual flexibility and strength-related issues that can impact their specific endurance sports. Working together with a carefully laid-out plan will not only help the athlete improve their performance, but also reduce the odds of getting training-related injuries.

Summary – Strength and Conditioning Practices in Rowing

May 16, 2011

Article Summary by Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Rowing is one of the most demanding of all endurance sports. While most of the energy contribution comes from aerobic metabolism, anaerobic qualities such as muscular strength and power are also key predictive qualities leading to overall rowing success. A survey was recently conducted in Great Britain among rowing coaches and strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches who worked with rowers. The results of this survey were published in the The Journal of Strength and Conditioning.

The British survey examined issues surrounding the use of strength training in rowing programs. Of the 54 questionnaires sent out, 32 responses were submitted for analysis. Twenty-two of the participants were rowing coaches, and the other 10 were S&C coaches. The average age of the coaches was 32 years and mean coaching experience was 10.5 years. 35% of the respondents coached Olympic level athletes; another 35% had coached at the National level; and the remainder coached at the Club, Regional, and University levels. 81% of the respondents held a Bachelors degree, and 34% a Masters degree.

30 of the 32 respondents reported that they conducted physical testing on their rowers. Testing included several key areas mentioned below including cardiovascular endurance, muscle strength, muscle power, flexibility, and speed.

Cardio included: 5km, 30 min., 16km, step test, 18km, and 1hr test

Muscle Strength included: “1RM squat, deadlift, benchpull,” “Concept II dynamometer (world class start testing protocol)”, and “1RM squat, push-pull, and deadlift”

Muscle Power included: “vertical jump and max Olympic lift,” “max power at 100 degrees/sec,” and “250-m ergometer,” “ergometer power strokes”

Flexibility included: “physio assessment protocol,” “sit and reach plus range of motion, joint tests,” “stretch bench tests,” “hamstring measuring,” and a “movement pattern tests.”

Speed Tests: “rating tests on water,” “ergometer sprints,” “racing on water and ergometers,” and “2,000m ergometer.”

30 of the 32 coaches said they used strength training in their programs, and all 32 coaches stated they believed strength training was a benefit to rowing performance. In-season season strength and power training was used by 26 of the coaches where frequency and intensity varied. 25% of the coaches surveyed lifted 2x/wk, 25% lifted 2-3x/wk, 25% lifted 3x/wk, 12.5% lifted 1-2x/wk, and 12.5% lifted 3-4x/wk. The number of repetitions performed during the in-season training also varied. 42% lifted using less than eight reps (3-6) per set, 26% lifted above eight reps per set, and the remaining 38% used a mix of lifts above and below eight reps per set. Strength training sessions varied from 30-75 minutes in length.

Off-season lifting was used by (responses) 25 coaches where days per week and repetitions varied as follows: 36% lifted 3x/wk, 28% lifted 2x/wk, 20% lifted 4x/wk, 4% lifted 1x/wk, and 12% lifted 2-4x/wk. The number of repetitions varied as follows; 16% lifted using less than eight reps (3-6) per set, 32% lifted above eight reps per set, and the remaining 52% used a mix of lifts above and below eight reps per set.

The survey also examined recovery time between lifting and rowing training. Specifically, coaches were asked to indicate the amount of recovery time they used between a high quality row following either an Olympic lift session or general strength session, and between the last Olympic and general lift session and a competition.

Olympic Lift Session & High Quality Row:

(Same Day) – 12%, (24 hrs) – 42%, (24-36 hrs) – 8 %, (36 hrs) – 26%, (48 hrs) – 12%

General Lift Session & High Quality Row:

(Same Day- 24h) – 17%, (24 hrs) – 48%, (24-36 hrs) – 11%, (36 hrs) – 13%, (48 hrs) – 11%

Olympic Lift Session & Competition:

(Same Day- 24h) – 0%, (24 hrs) – 0%, (24-36 hrs) – 0%, (36 to 48hrs) – 9%, (48 hrs) – 25%, (>48hrs) – 66%

General Lift Session & Competition:

(Same Day- 24h) – 0%, (24 hrs) – 0%, (24-36 hrs) – 0%, (36 to 48hrs) – 17%, (48 hrs) – 25%, (>48hrs) – 58%

The coaches were also asked to rank the most important weight-lifting exercises used within their training programs. The most commonly used exercises by ranking were the clean, the squat, and the deadlift. 16 of the 32 coaches used plyometrics as part of their training programs, while 31 out of 32 indicated that they used some form of flexibility training. All used static stretching.

The survey showed several key trends among rowing coaches in Britain. Physical testing is widely used to measure cardiovascular endurance, as well as muscular strength and power. Most coaches used Olympic lifts, and periodized their training plans. And generally, a 24 hour recovery was used between strength training and high quality rowing training, whereas 48 hours or greater was used between strength training and racing.

Reference:

Gee, TI, Olsen,PD, Berger, NJ, Golby,J, Thompson, KG,. Strength and Conditioning Practices in Rowing.

J Strength Cond Res 25(3): 668-682, 2011

Ease into the Catch Part 2 – Row2k Article

April 25, 2011

By Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Do you use momentum to get the last few inches of reach as you approach the catch? Or do you get there with freedom and ease? Your body, like all physical objects, follows the path of least resistance. Your catch length — the distance your hips and shoulders travel into the stern — can vary based on your flexibility and strength. Good flexibility and strength allows freedom and ease when approaching the catch, while deficits can create the need to use momentum to force your final, and less-than-ideal catch position.

The catch is a fundamental component of the rowing stroke. How we achieve this position varies based on our individual body type, flexibility, strength, and technique. With good flexibility and strength, the hip-shoulder position (fig. 1) can be set early in the recovery to create a strong body posture by the body-over position. Once this position is set, the remainder of the recovery simply involves sliding the hips into the catch position (fig. 2). Poor flexibility and / or strength can alter proper sequencing which can force the rower to use momentum to achieve adequate reach length. Changing the hip-shoulder relationship on the second half of the recovery can lead to a less powerful position at the catch, which in turn can increase the risk of training-related injuries.

Strength and flexibility imbalances limit your body’s ability to execute an effective and powerful rowing stroke. In other words, your brain will tell your body to take a rowing stroke, but your body can only produce the movement with the tools you have given it. Poor (inflexible and /or weak) tools give your body less effective options to perform a rowing stroke, which can result in a less powerful stroke as well as increased risk of injury. Better (strong and flexible) tools give your body more options to take a long and powerful stroke, and reduce your risk of injury.

Athletes with poor tools can still generate long and powerful strokes. The price of this trade-off, however, is an increased risk of training injuries that include lumbar disc herniation, low back pain, stress fractures, joint pain, etc. Since the body follows the path of least resistance, limitations in flexibility and strength can force the body into poor recovery postures, which may require the help of momentum to create the desired stroke length. Often times, the increased stroke length comes from excessive movement of the shoulders and back during the second part of the recovery, (fig.3). Stroke length is a concern for both coaches and athletes. When athletes have poor tools, they often need to use momentum to create the demanded increase in stroke length. Momentum can create a longer stroke but it is often less powerful. This occurs when the shoulders continue to travel into the stern while the hips have stopped moving into the bow (fig 4 -blue). Increasing the demands of the upper body and back (versus the hips and knees) at the catch can lead to increased injury risk.

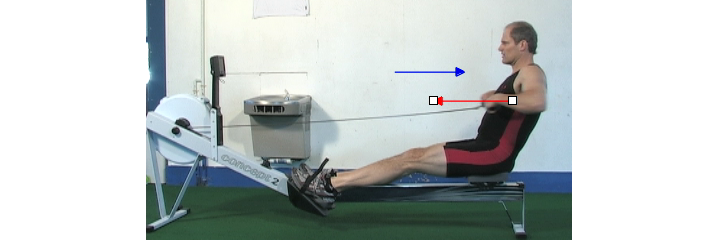

One simple way to measure your ability to get freely into the catch is to test yourself on an erg. Start out at the finish of the stroke, then proceed to the body-over position and pause for several seconds. Then pull yourself into the catch position. Hold the catch position for 5-10 seconds and have someone mark where your handle position is relative to the erg and mark the measured distance (fig 5 – red). Make sure that your hip-shoulder distance does not change as you approach the catch. Next, begin rowing for about 10-15 strokes and again measure the distance of your handle from the cage of the erg (fig 5 – yellow). If the handle positions are identical, then you have good flexibility and strength relative to your body posture at the catch. If the distance of your stroke increases (ie. the handle is closer to the cage) it may indicate you are using momentum to get those extra inches (fig. 4 – blue). It is also possible that you could also have a sequencing problem as you approach the catch (ie. your shoulders continue towards the catch through the whole recovery). In my experience, many rowers who dive with the body at the catch have moderate flexibility and strength imbalances that force poor sequencing as they approach the catch. This quick test can also be used as a general exercise to start working on improving the catch position without the use of momentum. Start at the finish of the stroke and pause at body-over position. Then slowly pull yourself into the catch as deeply as you can without changing the hip and shoulder relationship, which was set at the body-over position. Hold for 5 -10 seconds and repeat as necessary (10-15 reps is a good start).

Using momentum to achieve adequate stroke length leads to more tension on the recovery, reduced power on the drive, and an increased risk of injury. The best alternative is having strong and flexible tools. Staying strong and flexible will help you achieve a long and balanced stroke and excellent relaxation during the recovery – a requisite for a powerful drive and ideal rowing stroke.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Red = Catch Distance no Momentum

Yellow = Catch Distance while Rowing

Blue = Over-reaching/use of Momentum

Acceleration and Deceleration in Rowing – Row2k.com Feature Article

March 7, 2011

Don’t Forget your Springs when you’re Training your Engine and Pump.

By Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Rowing, like all sports, involves acceleration and deceleration of the body. To make this happen, our muscles assume the role of springs – they apply and absorb force to a given object. If we think of our body as a car, then our muscular system would be our engine and shock absorbers, our cardiovascular system would provide our fuel, and our bones, ligaments and tendons would serve as our frame. Endurance training tends to focus primarily on improving our engines and fuel – rightly so. However, the flip-side of this kind of conditioning is that we often neglect our shock absorbers. And weakness in the shock absorbers can then result in injuries to the frame.

Regardless of the activity, the majority of sports-related injuries occur at the peak points of acceleration or deceleration of the body. The forces required to control these sudden changes in body momentum can create an overwhelming stress to the frame. If your springs (muscle strength) are too weak to absorb to these forces, then your frame gets damaged. Based on the magnitude and repetition of the stresses involved, frame injuries could include joint pain (spine or extremities), stress or complete fractures, ruptured tendons or ligaments, and tendonitis. While the magnitude of acceleration and deceleration in a rowing stroke might not compare to that of cutting sports like football or basketball, typical rowing workouts do involve a high number repetitions performed at lower magnitudes of force. And, though more complete fractures or torn ligaments occur with higher magnitude sports, we do observe more overuse joint pain and spine-related injuries as well as stress fractures (ribs) and tendinosis issues in lower magnitude, higher repetitions sports like rowing. Therefore improving spring strength is essential to reducing risk-of-injury in both types of repetition sports.

Athletes in all sports can improve their base level of strength by performing that particular activity. Sometimes however, this is not enough to prevent injury to the frame. Additional training – sport-specific or resistance work — may be required to improve spring strength to an appropriate level. Springs, like the engine and fuel, must receive enough weekly stimuli to ensure appropriate strength to tolerate training volume and intensities. The need for additional strength becomes more critical as training intensity and volume increase. When we start to see training injuries such as low back pain, rib stress reactions / fractures, or other joint pain, there is a strong chance that part of this is due to insufficient strength in the shocks.

In rowing, the majority of training volume is done at lower ratings (22spm or lower), so the amount of stress in the shock is lower, while the volume is larger. And while the absolute strength required to control momentum at lower rating is less than at higher ratings, the volume is much greater, so the need for good strength-endurance is also important. The largest changes in body momentum occur at the catch (acceleration) and the finish (deceleration), and the magnitude increases as the rating goes up. By adding some extra sessions of power training at higher rates (24-28spm), we can improve the strength of the muscles used to help control body momentum. One session of higher rate training (typical weekly AT session) may not be enough to provide the necessary improvement in spring strength.

In racing season, there tends to be a larger volume of higher rating work on a weekly basis. In the off-season, however, there is a significant reduction in this type of work. Anaerobic threshold work is usually done at the 24-30SPM range. If you are only doing this type of work once a week, add a few extra sessions of higher rating work to keep your spring strength properly stressed. One suggestion would be to add in one or two sessions of burst work (8-10 strokes) at the 24-30 range. This can be done within a steady state workout, with long rest intervals between bursts. The rest intervals should be long enough that the steady state HR is not altered during a steady state session. If you strength train on land, try including a power session either on the erg or water, that coincides with your strength workout. Work to rest ratios will depend upon your goals for that session and time of year.

Body control is essential to achieving success in any sport. Having a balanced training program that also addresses your strength requirements will help you enjoy steady athletic improvement and reduce your risk of training-related injuries.

Ease Into The Catch – Row2k.com Feature Article

February 1, 2011

Ease Into The Catch

By Bob Kaehler MSPT, CSCS

Have you ever been told that you need to get more reach at the catch?

Whether you are 5’6” (167cm) or 6’4” (193cm), good reach at the catch is important. Proper hip flexibility and/or strength are essential to make this happen. When athletes do not have proper hip flexibility at the catch, quick solutions include either lowering the feet or sitting on a butt pad. A more effective and long-term approach is to identify your hip flexibility, and if necessary, improve it.

Lowering the feet and sitting on a butt pad are two common methods used to improving reach and ease of getting into the catch. However, both of these methods increase the vertical component of your rowing stroke and make your boat less stable. While these issues may not interest the recreational rower, they could result in loss of power and speed to the racer.

Changing foot positions is easy and relatively inconsequential on an erg. In boats, however, particularly the smaller boats (1X, 2X, 2-), it is difficult to adequately lower the feet because of the hull. In which case, a butt pad may be used. Rowers who lack ideal hip mobility can also increase their reach by bringing the shoulders deeper into the catch. This is done by increasing flexion (C-shape) in mid (thoracic spine) and low-back (lumbar spine). However, increasing the distance of the shoulders past the hips at the catch is not an ideal solution, as it increases stress on the passive tissues in the back (vertebrae, discs, and ribs). This additional stress can lead to back pain and/or rib fractures.

The ideal solution to improving reach at the catch is to improve hip flexibility. This will help not only eliminate the use of equipment and compromised technique, but also reduce the risk of injuries. To assess hip range of motion (ROM) at the catch, get on all fours with your feet (shoes off) placed over the edge of a staircase landing. This can also be done using a treatment table. Once you have your thighs and arms in a vertical starting position (Fig. 1), begin rocking backwards without moving your hand position. Push yourself back slightly with your hands, and then push back as far as you can (Fig. 2). Full range of motion for this test occurs when the ischial tubercles or sits bones (YELLOW MARKER) are able to touch both heels. If you are not able to reach this point, then you have limited hip flexion joint mobility, possibly caused by muscle inflexibility and/or loss of joint mobility.

Some athletes will find that they have better ROM on one side when compared to the other. Athletes with total hip replacements should consult with their surgeons before attempting to push to full ROM. This testing method can also be used as a corrective stretching exercise for those unable to achieve full range of motion with this test.

Another way to improve the same ROM is to do an assisted squat (Fig. 3). Grab onto a solid object or door frame, and drop down into the deepest squat position you can maintain. Place your feet about foot stretcher distance apart (Fig. 4). Make sure that you do not feel any knee or hip joint pain with these stretches. If you do, consult your physician before attempting to do this again.

Hip immobility is one of many imbalances that can prevent rowers from achieving an ideal, powerful stroke. Identifying and correcting these imbalances can reduce compensations elsewhere in the body (ie. increased low and mid-back flexion), and the need to adjust or use additional equipment. Most important, however, improved Body Balance will help athletes reduce their risk of injury and improve the overall effectiveness and enjoyment of their rowing.

Please contact Coach Kaehler with any questions or comments

VIDEO LINK OF THE MOVEMENTS IN THE FIGURES

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Proper “Core” Exercises can get you Back on the Erg, Pain-free! Rowing News Article

January 20, 2011

Indoor rowing can be a pain in the back. But it’s nothing that better core strength can’t fix.

By Robert Kaehler

“Because there is no change of direction on the ergometer, your muscular system is responsible for 100 percent of the energy that is required to change direction.”

One of the greatest things about rowing outdoors is hearing and feeling the water rushing beneath you on the recovery. The sudden increase in speed at the release is one of the most incredible and addictive sensations in our sport. There is none of this on the erg. Your trunk is dead weight every stroke—you stop the momentum into the bow, restart it as you head back to the catch, and repeat ad nauseum. Because there is no change of direction on the ergometer, your muscular system is responsible for 100 percent of the energy that is required to change direction from the finish to the recovery. On the water, that number is lower depending on how well you suspend your body weight through the drive and at the finish. The better your suspension, the less stress you place on your body. But the erg is the “truth teller.” It shows who has the internal tools (muscular strength) to handle the stress of the erg, and who does not, which manifests itself in lower-back pain.

Identifying your specific strength and flexibility deficits is best done in a one-on-one evaluation. However, there are several exercises you can do that can improve the strength you need to tolerate training on a standard erg. These include exercises that target the abdominal muscles and hamstrings and that strengthen the hip-flexion motion. You can improve abdominal strength by lying flat on your back with your legs straight, and then simply moving the trunk to an upright position (90 degrees or vertical). When your trunk is 45 degrees off the floor, try to place your low back in a straight position. You can change the intensity of this exercise by changing your hand and arm positions: having you arms reaching toward your toes is easiest; having them crossed behind your head is the most challenging. Once you can do 30 repetitions at the hardest level, start adding weight to the exercise.

You can improve hamstring strength with exercises known as bridges. Start by lying on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor, then raise your hips up off the floor in an effort to create a straight line with your shoulders, hips, and knees. Try holding this position for up to 10 seconds and then repeat up to 30 times. Make sure you keep your low back stable; if you experience stress in that area you are not engaging your supporting muscles correctly. Stop and seek proper instruction if that is the case.

If the bridges seem too easy, increase the degree of difficulty by placing your feet atop an exercise ball. You can perform the hip-flexion motion while on your back with your arms extended and secured to a solid object. Proceed by pulling your knees toward your elbows. When you do so, your trunk will curl up while your knees bend toward the chest. Once you are able to perform 30 repetitions of this exercise, you can either add weight to your ankles or try the same motion while hanging from a pull-up bar. Reducing stress on the passive tissue (discs and ligaments) of the low back while training on an ergometer is key to remaining healthy during training, and improving your trunk strength is the best way to achieve it.

Increasing Body Momentum - Drive

Muscular System Must Provide 100% Effort for Change of Direction - Standard Erg

Improving your Hamstring Flexibility

January 2, 2011

By Bob Kaehler

Have you ever complained that your hamstrings always feel tight? No matter how much you stretch your hamstrings, they never seem to become more flexible?

Flexibility is a key factor in allowing you to get into the best body position at the catch, and in achieving a long, strong, and powerful rowing stroke. Tight hamstrings limit your ability to achieve this ideal body position. Static and dynamic stretching are two effective methods used to improve your flexibility. Long term changes to flexibility require consistent effort. The hamstrings are no exception.

Static stretching has long been used as a way to increase flexibility in muscles, and improve range of motion in joints. This type of stretching is done without movement (i.e. you remain still). The force or pressure is applied to the area being stretched by an outside force, such as a wall, strap or another person.

Studies have shown that the biggest improvements in ranges of motion occur when the end range stretch position is held for longer periods of time (10+ seconds, o r longer). The stretch position should be repeated multiple times (5-10) for greater results. For athletes looking to actually get a permanent change in their flexibility, consistency becomes a key factor. Stretching should be done every day, and if possible, several times a day for even greater results.

Recent studies also confirm that static stretching does reduce your explosive strength immediately following the stretching period (up to an hour or so). Therefore this method is best used after training sessions, not before. A simple, yet effective, method of statically stretching hamstrings involves using a door frame. Simply lie on your back next to doorway with your feet facing the opening. Slide the non-stretching leg through the doorway, then place the stretch side foot up onto the molding. Extend the knee joint of the leg being stretched so it becomes straight. You will probably need to adjust the distance of your hips from the wall to get the proper stretch tension. Ensure your tail bone does not come off the floor once you are in the appropriate stretch position.

Another approach to stretching is dynamic. Dynamic stretching is an active method where you provide the energy (i.e. you move) to produce the desired stretch. Ensure, however, that you do not exceed your normal end range for the movement otherwise it becomes a ballistic stretch. Dynamic stretches usually mimic the same sporting form that you are about to perform. To produce a good hamstring stretch, simply do a quick body-over pause (1-2 second hold), whether you are on the water or on an erg. Keep your low back in a firm upright position with the spine as straight as possible. Slumping at the low back eliminates much of the stretch on the hamstrings, so be aware of your posture. You should feel a good stretch in the back of the knees (bottom of the hamstrings) when you are in the body over pause position. If you do not you either have very good hamstring mobility or you are slumping in your low back. The point of dynamic stretching is to warm-up your body before training and racing; not to force your range of motion beyond your natural limits. Practice this form of stretching on a regular basis before adding it to your regular pre-race warm-up routine.

Dynamic stretching is ideal for warming-up muscles and joints prior to training sessions and racing. Its purpose is to prepare the tissue to properly handle the stresses of the activity. Static stretching, on the other hand, is ideal for making permanent changes (i.e. increasing) range of motion, and is best done separate from training and racing sessions.

With proper technique, combining both static and dynamic stretches into your training program is an effective way to prepare for training properly, to reduce your risk of injury, and to improve your baseline flexibility.

Balance your rowing program – Row 2k Article

December 8, 2010

Balance your rowing program – Row 2k Article by Bob Kaehler

Do you feel the need to try and balance out your rowing program by cross-training? Most of us want to be better, stronger and healthier rowers. However our commitments to work, family, and other life issues make it hard to find the time to get in additional non-rowing workouts. Simply adding two or three 20-minute strength/core training sessions will add balance to your current program, and lead to better, stronger and healthier rowing. These sessions can be used as a quick warm-up before training, or can be done by as a separate training session.

You can create your own 20-minute balancing program by doing some strengthening exercises that target the opposing (antagonist) muscles to those which are used on the drive of the rowing stroke. We can break up these exercises into the upper body and trunk, and the lower body. While the major muscles (quads, glutes, low back, and rhomboids )used on the drive of the stroke are aggressively working to propel the boat/erg forward, the antagonists are working to provide support and control of the body, and work at a lower level of intensity. The antagonist muscles include the hamstrings, upper and lower abdominals, hip flexors and pectoral muscles to name a few. These antagonist muscles play an important role during the drive of the stroke by maintaining a strong body position. The opposition work the agonists provide creates the platform needed for complete body suspension during the drive.

Adding simple trunk and upper body exercises to your routine, such as push-ups, pull-ups, and sit-ups, is an effective way to start working on your balance. If full body pull-ups are too difficult, use assistance until you build your strength. There are several options for assistance including the use of bands (Ironwoody), using assistive pull-up machines (Gravitron), or by doing lat pull downs. Push-ups can be done on the knees, at full body length, by placing a weight (plate) on your back placed between the shoulder blades, or you can do bench presses. Sit-ups can be done with or without weight placed on the chest, or you can use an incline sit-up bench. When starting out, a good goal is to be able to complete 30 repetitions of each exercise. Then you can increase the intensity level by removing the assistance or adding weight to the movement.

Exercises that balance the lower body should target the opposing muscles and include the hamstrings, lower abs and hips. While many exercises target these muscle groups, starting simply is always a good idea. Some effective exercises include bicycling, scullers, bridges, and leg lifts. These exercises can be done with or without the use of resistance, however you must be able to maintain good control of the low back during the exercise movement before adding any weight to the legs. When doing bridges or leg lifts, check the starting position of your low back (amount of arch or hallow in your low back) before you start the exercise. A good goal for both these exercises is to maintain the same amount of arch or hollow in the low spine throughout the exercise movement. Control the range of motion of each exercise by monitoring your spine position. Once you have enough strength you will be able to complete a full exercise movement. Limit how far you lower your legs with the leg lifts, and how high you move (extend) your hips off the floor when bridging. As you gain strength in the trunk, your range of motion will increase.

For bicycling and scullers, your low spine will need to curl when doing these exercises. So your goal is to improve endurance and strength. We do this by first increasing volume then increasing intensity (adding weight). Once you can do 30 repetitions with good form, consider adding additional resistance to increase the intensity. A good starting point is completing 30 repetitions without resting before adding resistance to the legs or arms.

Adding just a few 20 minute sessions of balancing exercises to your weekly training program is a simple yet effective way to improve your strength, fitness and overall rowing health.

Rowing News – November Article – Cram Session

November 15, 2010

Build strength, endurance, and power by combining your weights and water workouts.

By Bob Kaehler

While we all want to be stronger and faster, finding time to add strength training into your current rowing program is a common problem. One option is to combine your strength training and rowing into one session. Choosing which comes first depends on your goals for the workout. Some prefer rowing after their muscles are already fatigued from a strength-training session. Others will want to row while they are fresh. And there will be some who are fine alternating which comes first.

Getting your strength-training session in before you row is a great way to warm up. It also helps improve your strength and flexibility. Circuit training with light (10 to 30 percent of body weight) to moderate (30 to 65 percent) weight is an excellent way to stress the neuromuscular system without over taxing it just before a session on the water or erg. Strength training using heavier resistance (80 percent of body weight) puts greater stress on the neuromuscular system, which can impede proper rowing technique. Plan on getting your row out of the way first if you are going to be combining a heavy strength-training session with a paddle.

A short to moderate (20- to 40-minute) strength-training session improves muscular endurance, strength, and power under conditions of fatigue. Training your muscles when fatigued is an excellent way to improve muscular endurance while simulating end-of-race conditions. Make sure you factor in your level of fatigue when choosing the resistance for a particular session. I recommend a routine that features light to moderate weights following a row; lifting heavy weights immediately after a rowing session increases the risk of injury. But if you absolutely must combine heavy weights with a session on the water, select resistance levels that are less than what you would do when fresh.

For those who have never combined rowing and strength training together in one session, I recommend giving your body eight to 12 weeks to adjust. Start by rowing for 25 to 30 minutes and then lifting for 20-25-minutes, or vice versa. It’s up to you what you do first, but if you’re new to strength training, consider beginning with it. If you are resuming training after a layoff, try to keep the total combined strength and rowing session to no more than 30 or 40 minutes. Remember when starting out to choose strength exercises that you are familiar with and keep the load on the lower side (10 to 30 percent of body weight). More experienced athletes can increase the volume based on their current training programs and levels of fitness.

Performing at your best requires that you train both the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. Adding land-based strength training to your current program helps to improve the strength and power of your rowing stroke. The research shows that gains in strength occur when strength training and endurance sports training sessions are combined. Regardless of the net effect on your rowing performance, combining strength-training and rowing sessions is an excellent way to improve strength, endurance, and power.